Excavation And Research

Architect Dennis Holloway’s 3-D drawings of Chimney Rock

During the summers of 1970 through 1972, the USDA Forest Service contracted to “survey, excavate, and restore” ancient structures at Chimney Rock for public display. The sites excavated were the Great House Pueblo, the Great Kiva, and the Ridge House. These excavations barely tapped the surface. There are more than 100 sites in Chimney Rock National Monument.

It is assumed the distinct architectural styles of the Chimney Rock Great House, on Chimney Rock’s High Mesa, was built by people who had different family organizations and construction ideas than the local people. This does not represent the gradual change expected within a common culture and leads to questions about the presence of and relationships between different cultural groups within the Monument. Were some residents local, others local leaders or intermediaries, and still others non-local elites or priests?

Uncover the story

Early work at Chimney Rock was undertaken by Jean Allard Jeancon, curator of Archaeology and Ethnology in the 1920s at the Colorado State

Historical and Natural History Society. He and Frank Roberts excavated at Chimney Rock from 1922 to 1926. Frank W. Eddy, recently retired professor of Anthropology, University of Colorado at Boulder, was principal excavator at Chimney Rock in the 1970s. The legacy of University of Colorado research continues. During the 2009 field season, portions of the Chimney Rock Great House were excavated by Stephen Lekson and Brenda Todd.

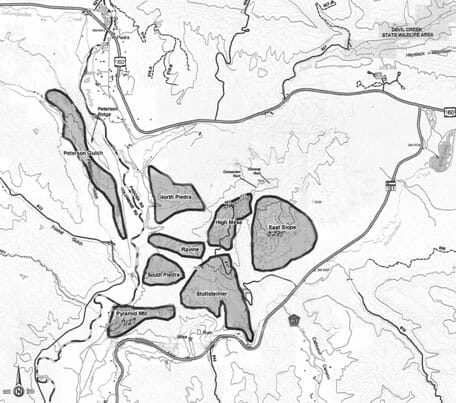

Chimney Rock’s eight villages are known as North Piedra, South Piedra, Ravine, Pyramid Mountain, Stollsteimer Mesa, the High Mesa, the East Slope, and Peterson Gulch. The map shows the village sites within the Monument.

Preserve for the future

Why not excavate the remaining sites and find answers to the questions that previous digs have raised? Lack of funding is the obvious answer. Sensitivity to modern day Puebloans’ feelings and beliefs relating to the Monument is another. The primary reason to leave the vast majority of Chimney Rock’s history undisturbed is the liklihood that research and testing methods will continue to improve as they have since the first spade unearthed an artifact at Chimney Rock. As the field of archaeology advances, we can look back and understand much has been lost through lack of knowledge or lack of technological expertise. For example, wood samples were not collected during the 1920s excavations; today, dendrochronology is an invaluable tool for dating sites and construction phases. Corn samples collected during the 2009 field season could be genetically typed; local cultivation was shown through chemical analysis. Leaving portions of the site unexcavated will allow future researchers to apply new techniques we can’t even imagine today.